Protected: Personal Reflection and Self-Evaluation

4 04 2009Comments : Enter your password to view comments.

Categories : Uncategorized

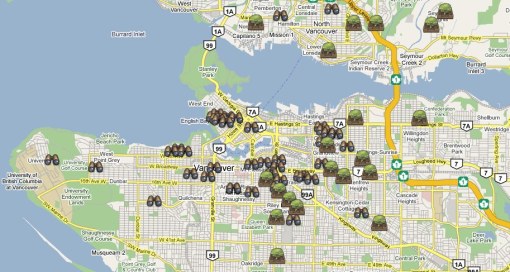

Models of Urban Agriculture Elsewhere

31 03 2009Vancouver is a city already well-noted for its urban agriculture project, and recently made national news by very openly coming up with a new bylaw for keeping chickens for egg production within city limits. Its most established promoter has been City Farmer (two parallel sites), an organization that has been promoting urban agriculture for thirty years. They teach, put workshops about composting or vermiculture on and, interestingly, operate an online map whereby people in Vancouver may attach their name and situation to a map of the city and indicate whether you have room in your backyard to share the chores with, or whether you have the desire to do that work at someone else’s backyard. Sharing Projects is a fairly advanced Google Map site, offering more in-map information such as the ability to respond to “sites” directly. In some ways, it is e-dentifying Space in reverse, but it still is attempting to identify (privately-owned) community assets for agricultural purposes.

While riding German intercity or S-Bahn trains, one often notices that alongside the tracks large swaths of land are devoted to very intense agricultural and garden plots. These allotment gardens were originally intended to serve as a way in which to help and give food and fresh air opportunities for the poorest members of urban populations who increasingly lived in crowded, unsanitary and unsafe conditions in newly industrialising cities (Drescher 2001). Allotment gardens played important roles during and following the two world wars, offering cities a greater food security, and today, some 1.4 million organized allotment gardens still exist in and around cities, and while many plots are used for recreation, food production is still seen as being an important outcome.

City councils provide the land and a watering system, while individual garden owners (who must be members of the German Leisure Garden Federation) pay a small rental fee every year for use of the plot and often erect small sheds on site to store individual garden tools. These gardens are an excellent way to provide urban dwellers who otherwise would not have access to garden space a chance to practice their green thumbs, while doing so in a friendly, social and natural setting on land that otherwise would not have been used for anything as productive.

At a more extreme and hypothetical end, Front Studio architects out of New York City envisioned a transformed Philadelphia as its empty lots and abandoned buildings were transformed into its own “agricultural urbanism”. From their website, Farmadelphia intended to create “juxtapositions between farm and city that challenges its residents to revitalize their surroundings and daily lives.” It “empowers”, creates “localized centers of activity” and strengthens “an overall sense of pride and commitment in the community”.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Germany, Philadelphia, urban-agriculture, Vancouver

Food, Cities and Urban Agriculture – Where are we?

31 03 2009In late 2007, Toronto Public Health released a discussion paper on the potential for Toronto to develop a broad and effective food strategy. As a discussion piece, it built off of the Toronto Food Charter that was adopted by City Council in 2001 to guide economic, social and environmental policy surrounding food issues. It focuses on broad issues surrounding food security, whereas the 2007 discussion of a food strategy for the city takes a more in-depth look at this multi-faceted approach to food in a way in which to implement the goals of the Charter. Echoing the Charter, the implementation purposes are to:

Improve health,

Promote economic development,

Promote social justice, Protect the environment, and

Reflect and celebrate community diversity (Toronto Public Health 2007, p. 2).

The discussion paper recognizes that food is a vital component to the social, environmental and economic well-being of the city, and especially, its production offers many ways in which to increase the overall sustainability of the city. Little formal attention is paid by the City of Toronto to the economic, social and environmental opportunities that urban agriculture presents to the City and its residents, and as such has not identified spaces where agricultural activity, on large or small scales, may be engaged.

Our relationship with food represents one of the most intimate, and thus profoundly local, ones we have. Recognizing this, cities’ agricultural production has become an area of increased attention since the 1987 Brundtland Report, commonly called Our Common Future, that recommended governments support urban agriculture “to improve the nutritional and health standards of the poor, help their family budgets, enable them to earn some additional income and provide employment” among other environmental benefits (World Commission on Environment and Development 1987, p. 254). For people with higher incomes and in more stable urban areas, deciding to have a part in the production of their own food has been a form of recreation and enjoyment as well as improving their own food security. The land potential for agricultural production will be noted below, but the economic potential is great as well: Roberts estimates that intensive agriculture on underused land in Toronto may yield $100,000 worth of high value crops per acre (2001, p. 26). Indeed, “in contrast to pure greenspace or parks, which taxpayers generally have to finance, urban agriculture can be a functioning business that pays for itself” (Smit, in Halweil 2004, p. 93), which is good news for the economic side of the sustainability convergence in cities. All members of society, and the City coffers itself, can benefit from activating and utilizing the underutilized land around them.

The land on which Toronto sits is some of the most productive and fruitful agricultural land in the country, giving credence to the somewhat popular piece of trivia that, on a clear day, one can see one-third of the entire country’s Class One farmland from the top of the CN Tower in downtown Toronto (Toronto Public Health 2007, p. 9).However, much of that land is disappearing: over a period of ten years, from 1991-2001, 107,000 acres of farmland in the Greater Toronto Area were taken out of production and turned into roads, residential subdivisions and large commercial or industrial centres (Walton 2003, p. 6). Once this land is removed from agricultural production, it cannot be reconverted by similar large-scale agricultural methods and the reliance on food shipped from elsewhere increases.

(photo by Ann E on Flickr.com)

(photo by Ann E on Flickr.com)

Housing and food production do not have to compete for the same land: food can be grown where housing would never go: in hydro corridors, on hilly land, and in the vacant spaces between land uses. This would maximize the value and production of the land while providing environmental benefits to the surrounding areas – generating fresh oxygen, soaking up stormwater, cooling localized areas by evaporating excess water, and taking in compost (Roberts, 2001). Still, the challenge of urban food production remains one of space. Many urban residents, particularly in dense downtown neighbourhoods and condominium developments, do not have the land necessary to engage in food production, or they do not realize the food producing viability of the space that they do have. Toronto Public Health (2007, pp. 9-10) notes that, although there are upwards of 4,500 publicly-owned garden plots within city limits (and countless privately-owned gardens), very little of its residents’ food consumption comes from within the city. The potential is there: 18% of Toronto’s land area is green space, considerable land is underutilized (especially that land for automobile travel and storage), and 5,000 hectares of rooftops could potentially be available for greening and food production (Toronto Public Health 2007, p. 9). Even for a small amount of that land (or building space) used for food production can affect food security a great deal; land can yield a great deal of food if properly kept up. For example, Roberts notes that an intensified garden on an individual’s residential property a mere 20 square feet large may yield upwards of 200 pounds of vegetables per season (2001, p. 26).

Toronto is very well-positioned to be a North American urban agriculture leader. Encompassing the entire city is the Greenbelt, the province of Ontario’s response to rapid growth in the region and the subsequent loss of natural and traditional landscapes. Through the Greenbelt Plan, regional and municipal governments, private developers and the province itself are informed “where urbanization should not occur in order to provide permanent protection to the agricultural land base and the ecological features and functions occurring on this landscape” (Ontario 2005, s. 1.0). While not formally within Greenbelt boundaries, Toronto is positioned to be a major “external connection” in “the broader agricultural system and economy of southern Ontario” that the Greenbelt Plan is encouraged plan appropriately with to maintain and strengthen both the functional and economic connections (Ontario 2005, s. 3.1.5). In the regional economy that the Greater Toronto Area and broader Greater Golden Horseshoe exist within, strengthening the systems of one part must be met with similar approaches elsewhere to maintain a balance and equitable distribution of benefits. This must occur with Toronto’s agricultural system; it must also begin to be afforded the same protections and prominence featured just beyond the City’s borders.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : Toronto, urban-agriculture

A short blurb on the blog design

28 03 2009The colour scheme and design of the site is symbolic of what it represents. Grey, normally a dull and lackluster colour on a website, serves a purpose here, drawing the eye upward to the title banner and title and brief description of the project there. Bursting with life, the red and greens are the hope of this project, the ‘e-dentified’ plot of land in the surrounding grey-ness that has been converted to a more intensive, sustainable and dare-I-say appropriate land use.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : design

Linking to Urban Sustainability

26 03 2009In a society that is increasingly connected to the places and events happening in the faraway corners of the world via the Internet and instant communication through other online and networked technologies, it seems counterintuitive that the most profound impacts on sustainability will and must happen at the local level. However, even as the many media bring home images and stories of faraway environmental and ecological stresses that profoundly affect people’s social and economic livelihoods, as well as their physical well-being and very survival, it is important to remember that those stresses on sustainability in all its facets are happening in others’ “local” areas. While recognizing the global consequences of one’s actions, the response is much more effective when approached at a local level (as noted in Bellows & Hamm, 2001; Campbell, 1996; Robinson, 2009).

Humans are inherently connected to and yet apart of the ecological principles and processes that dictate everyday life, yet our increasingly “sequestered” urban habitats do not allow us easy and direct access to these ecological environments, effectively insulating us from the burdens we place on the planet (Mullinix et al., 2008, p. 3). In order to sustain large urban populations, a great many of these burdens come from large-scale, industrialized agri-food systems that rely heavily on chemicals and monocultures to be viable. Food is not viewed as a necessary human need with an ecological function, but as a commodity where a vertical integration of production, labour, transportation and marketing renders food to be mere commodities to be bought and sold. Lister describes this current state of the food system as one that is ruled by commerce and “not the respectful laws of nature”, leading to wholly placeless and ecologically-devalued food (2007, p. 159).

It is through agricultural production in cities that a revaluing of food may occur. By returning land within cities to food production, we may help reverse the urban-rural divide that shifted agriculture almost exclusively to the open spaces on the fringes of cities while paving over and building up the fertile farmlands from which most Canadian cities developed. This will bring about many other positive effects, as Mullinix et al. note (2008, pp. 4-5), including addressing an aging farmer demographic, deconsolidating industrial food systems to allow more people access to its profits and successes, and the logistical benefits of actually growing food where the end-users will consume it. The importance of the local place is articulated well by Walton who argues for a healthy agricultural industry in and near the City of Toronto because

[y]ou can build a house almost anywhere; you cannot grow a peach anywhere. As part of the creation of federal or provincial policy on agriculture, there needs to be a review of what is grown where, what can be grown where, how much needs to be grown to satisfy the populations needs, and what strategy is required to achieve stated goals (2003, pp. 19-20).

The ultimate goal of this project is to help move the “urban agriculture” approach that already exists in the City of Toronto through its patchwork network of community garden plots, green rooftops and backyards to one of an “agricultural urbanism” whereby “a comprehensive, ecologically-based, systems approach to agri-food system planning and implementation [is] designed to meaningfully advance human enterprise sustainability” (Mullinix et al., 2008, p. 7). By identifying (or e-dentifying) the spaces used and available for food production, pressure may begin to mount to change how the City of Toronto and its residents fundamentally view food production and the urban spaces that surround them. The spaces, I hypothesize, for coordinated, semi-coordinated and uncoordinated food production to form a broader agricultural system do exist within the urbanized area; the challenge is actually identifying them, recognizing their opportunities and constraints, and engaging the correct people—their owners, neighbours and city officials—and educating them to the benefits of activating them as agricultural space. I use the word “system” because, ultimately, the disparate garden plots and cultivated rooftops can work in harmony to address food security and urban sustainability issues, whether they are part of City of Toronto-coordinated agricultural system, a community group, or private citizens reducing the numbers of tomatoes and carrots needed to be purchased at the grocery store every week.

(photo by tigerlillyshop from Flickr.com)

Graphically displaying the potential, and in some cases, already fulfilled capacity of Toronto’s agricultural food production is a vital component to working towards this goal of an agricultural urbanism. The city is not a barren place, and its potential for supplying a considerable amount of food for its residents represents a significant step forward in its overall sustainability planning efforts. The implications for environmental sustainability are many, as ‘food miles’—the distances food must travel to get from field to table—are eliminated and the grower has complete control over the production of the crops thereby potentially eliminating environmentally-damaging pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers.

From the economic standpoint, individuals growing food in urban areas help keep money in the local economy, freeing up spending for other sectors. Further along that vein, “in contrast to pure greenspace or parks, which taxpayers generally have to finance, urban agriculture can be a functioning business that pays for itself” (Smit, in Halweil, 2004, p. 93). In fact, Roberts (2001, p. 26) estimates that intensive agriculture on underused land in Toronto (for example along utility corridors) may net $100,000 worth of high-value crops per acre. Socially, food has long been a source of community empowerment (Gottlieb & Fisher, 1996, p. 26) as well as a gathering point for families and communities at kitchen tables, restaurants, community gardens or markets.

Most cities do not put much emphasis on organizational, administrative and governance factors vital to sustainable development, however important these aspects are to fully implementing sustainability policies and putting them into practice. Dale offers a solution where “a more appropriate role for governments in the twenty-first century may well be to support processes that increase social capital as this will ultimately lead to a strengthening of both ecological and economic capital” (2001, p. 158).

Asset-based community development, as Leviten-Reid argues, gives credence to the positive aspects of interdepartmental and intergovernmental support for neighbourhoods (2006, p. 4). The collaboration by residents in identifying those assets in their communities deemed to be important for (in this case) urban food production cycles upward through the local government, giving those departments and agencies with active interest in such an endeavour—City Planning, Social Development, the Toronto Environment Office, Parks, Forestry & Recreation, and Public Health’s Food Policy Council—the chance to collaborate and share the risks “where they are joined upstream” rather than contending with resulting challenges “downstream” alone (Bulthuis, in Leviten-Reid 2006, p. 4).

As Dale notes with regard to sustainable development, food systems must be planned in ways “that [work] in synergy with ecosystem functions and processes, recognizing natural limits and maintaining rather than exploiting resilience and diversity” (2001, p. 147). Toronto is a city rich in varied ecosystems and diversity, yet has pushed its natural limits considerably. At the same time, it has a lot of work to do within its social and economic limits, and must work to become a sustainable community once again. The following emerged from the President’s Council on Sustainable Development in 1997, and quoted by Green and Haines, that succinctly lays out a system of well being that cities will be wise to follow:

Sustainable communities are cities and towns that prosper because people work together to produce a high quality of life that they want to sustain and constantly improve. They are communities that flourish because they build a mutually supportive, dynamic balance between social well-being, economic opportunity, and environmental quality (2002, p. 185).

It can only play a small role, but by having people engaged and participating in their communities surrounding food and through e-dentifying Space, Toronto will be better positioned for the very uncertain future.

Comments : Leave a Comment »

Categories : ecology, sustainability, urban-agriculture

An Introduction to e-dentifying Space

13 02 2009Welcome to e-dentifying Space, the convergence of community engagement and collaboration through web 2.0 tools to affect urban sustainability in Toronto by identifying land (or other spaces!) that may be used for urban food production. Sitting on some of the country’s most fertile topsoil, Toronto’s agricultural potential is great, but wholly underutilized. It is an untapped source of sustainability in the City, one that has the opportunities to move beyond its confines of private backyard plots and scattered community gardens and into vast tracks of land in parks, along roadways, near hydro lines, and on the tops of roofs where little of economic, social or environmental value currently exists.

“Where do you want to grow?”

Toronto is regularly referred to as a city of neighbourhoods, and those neighbourhoods are full of identifiable assets—from the community infrastructure of physical facilities to more intangible programming and social networks, all of which serve to improve the quality of people’s lives (Arundel et al 2005, p. 10). In most cases, it is not up to the planner with a privilege of broader knowledge to identify these assets as that task has fallen, probably most appropriately, to the communities themselves. This “narrative” produced by community plans is especially prevalent in heritage planning and, most importantly for this project, sustainability and long-term visioning planning (Foth et al 2008). Interestingly, the democratization of planning has paralleled a similar democratization of media and information through the internet, and its intersection with sustainability, and in particular food production, represents in important convergence of ideas and visions for more inclusive, healthy and represented citizens and cities.

(photo by Jen Chan of Flickr.com)

(photo by Jen Chan of Flickr.com)

Foth et al (2008) describe these public narratives as having the abilities to “make a lasting ‘place’ out of public space, allowing people to connect with these narratives in either a physical or virtual way”. This, in many ways, succinctly sums up ultimate goals of the project: to connect people with each other and their city digitally, building on the stories of others while creating their own, and from them, moving toward a place where online connection is turned into a physical one, garden plot by garden plot, property by property, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, place by place. There are intuitively thousands of un- or under-utilized pieces of property in the City of Toronto, but identifying them as such can prove difficult. A space that may have food production potential in one person’s view may bring with it potential challenges and conflicts that can initially be navigated through the online collaborative discussion on the website before proceeding offline to affect real physical change. In this case, the process of collaboration, building community capital and strengthening social networks through asset identification and discussion is just as important as important to affecting sustainability in Toronto as the outcomes of ecological systems restoration through food production, policy change and government acceptance and support of this ongoing process of re-agriculturalizing the urbanism of the city.

This site and the associated map are very much in a beta phase, and will likely show some kinks along the way. Please bear with me as I engage in new-found technological skills to try to correct them. Thanks! In addition, gaps in the research are expected given the broad scope of urban agriculture, community identification of assets and of the emerging nature of the web 2.0 and online participation within it.

Comments : 1 Comment »

Categories : blog-intro

(photo from

(photo from